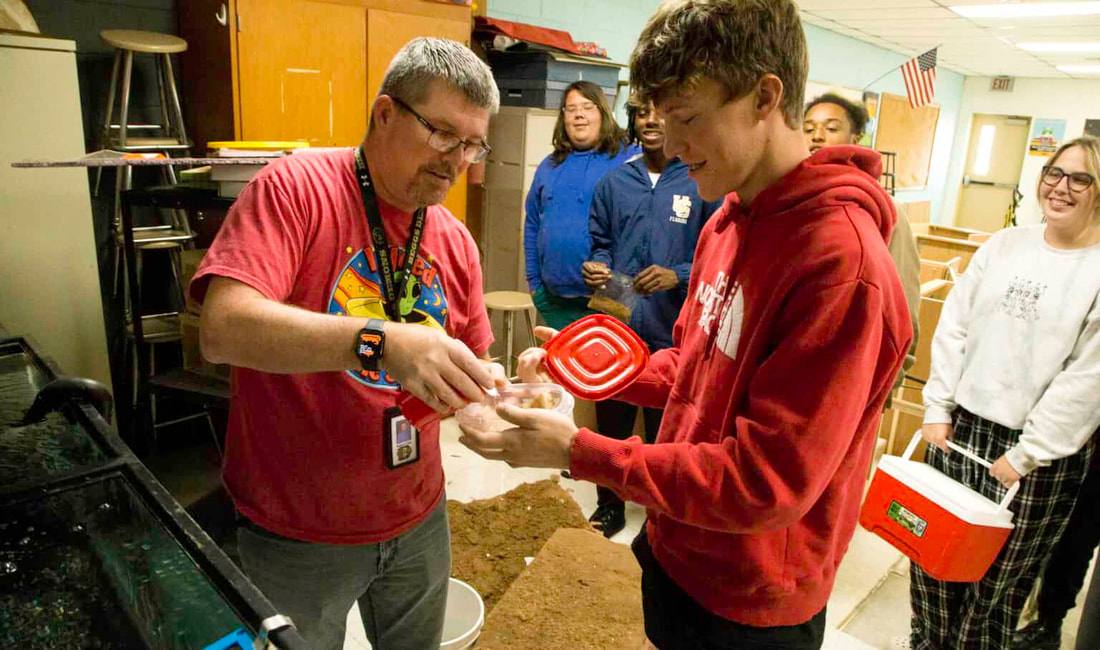

Trout in The Classroom provides lessons from elementary school art to advanced marine biologyBy KELLY BOSTIAN For the CCOF Nature is unpredictable and far from perfect, especially where people are involved. If Oklahoma students have pulled anything from Trout in The Classroom projects over the past eleven years that is at least part of the lesson. Now in its eleventh year, the program offered through private donors and volunteers with Tulsa-based Trout Unlimited Chapter 420 involves 14 schools from Owasso to Henryetta, with most in the Tulsa area, according to organizer Scott Hood. Teachers devise their own lessons around the $1,200 worth of equipment and fish provided at no cost to the schools, he said. Lessons have ranged from elementary school art classes and calendar observations to advanced high school biology, chemistry, and math lessons, he said. It started with Hood learning about the program during a national Trout Unlimited conference and then bumping into a group of teachers back home. “It was after a TU meeting, there was a group of teachers in another room and I just dropped in and said, ‘hey, would anyone be interested in this Trout in the Classroom project?’ and Diana Nunes from East Central High School said ‘yes,’” Hood said. She operated the first and only tank during the 2011-2012 school year. It has grown a few tanks here and there annually, as interest and funding allowed, to 14 tanks and 5,000 eggs this year. Projects end with springtime field trips to the Lower Illinois River, where students release the trout they’ve raised in the classroom, if any survived, and learn about river ecology, and fishing while they’re there. From start to finish, the projects are fraught with potential issues, but Hood pointed out that nothing in nature is guaranteed. Trout lay thousands of eggs for a few to survive. This project dispersed 5,000 eggs among 14 schools this year—giving each school roughly 300-400 eggs. The measurements involve plastic containers, a plastic spoon, and are not exact. A dozen volunteers waited in Hood’s office one morning last week for a FedEx truck only to learn the delivery was delayed for a day. The next day 10 volunteers waited with small coolers of their own to carry ice and a couple of tablespoons of eggs and a wet paper towel inside a small sealed container to their assigned school. It can be tricky to arrange deliveries. Volunteers have to be patient. It was easier when FedEx still had guaranteed 10:30 a.m. deliveries, but even then Hood once went to FedEx to retrieve the eggs. They are shipped overnight from Tacoma, Wash. in a boxed Styrofoam cooler large enough to hold a 12-pack, but with small sections inside to hold crushed ice and small parcels of eggs. The 5,000 shipped to Tulsa wouldn’t have filled a 12-ounce can. “We did have to go looking for it one time it was lost,” Hood said with a chuckle. “I told them to look for any box that was dripping. They found it. It was dripping.” Those eggs were still cold and perfectly fine, he said. “We’ve had classes that had almost every egg hatch and most of the fry released and we’ve also had some catastrophic failures over the years,” he said. The tanks are equipped with chillers to keep the water just right for the species that love cool clear-water streams. One class left the sensor outside the tank after cleaning it, so the chiller kept trying to cool the water. They ended up with frozen fish.

“At one school they had a construction project going over a long weekend. They didn’t know about it, but the power was turned off for three days. When they came back on Tuesday the tank was running but all their fish were dead. At first, they had no idea what could have happened.” Many more are successful than fail it’s just that the catastrophes leave a mark. Students do learn how fish thrive or struggle under relatively minor changes in temperature or water chemistry, he said.. The education is all up to the different groups of kids and dedicated teachers who must monitor the tanks regularly—even over the holiday breaks, he said. “The main thing is learning about the value of clean water, but we’ve had so many kids, you can just see their world open up,” he said. “They’ve never been around wildlife or tried to take care of an animal other than maybe a dog or a cat. Some have never been out of the city, so it really can make memories for a lifetime.” Kelly Bostian is an independent journalist writing for The Conservation Coalition of Oklahoma Foundation, a 501c3 non-profit dedicated to education and outreach on conservation issues facing Oklahomans. To learn more about what we do and to support Kelly’s work, see the About the CCOF page.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

Conservation Coalition of Oklahoma

P.O. Box 2751

Oklahoma City, OK 73101

[email protected]